Although the International Monetary Fund (IMF) claims that poverty reduction is one of its objectives, some studies show that IMF borrower countries experience higher rates of poverty. This paper investigates the effects of IMF loan conditions on poverty. Using a sample of 81 developing countries from 1986 to 2016, we find that IMF loan arrangements containing structural reforms contribute to more people getting trapped in the poverty cycle, as the reforms involve deep and comprehensive changes that tend to raise unemployment, lower government revenue, increase costs of basic services, and restructure tax collection, pensions, and social security programmes. Conversely, we observe that loan arrangements promoting stabilisation reforms have less impact on the poor because borrower states hold more discretion over their macroeconomic targets. Further, we disaggregate structural reforms to identify the particular policies that increase poverty. Our findings are robust to different specifications and indicate how IMF loan arrangements affect poverty in the developing world.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the past few decades, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has maintained that it is committed to lessening poverty in the developing world. The IMF’s provision of concessional financial support through the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust for low-income countries is evidence of the Fund’s interest in lowering poverty (IMF 2021). The Fund’s recent endorsement of fiscal stimulus measures to protect lives and livelihoods against COVID-19 further suggests its concern about people most at risk of economic hardship (Fiscal Monitor 2020). Although the IMF is not a unitary actor, and its management, research department, and staff may have different views on how to design lending programmes to best address poverty, the IMF claims that its programmes seek to achieve poverty reduction and growth (IMF 2021).

Some studies also seem to back the IMF’s position, noting that since the Great Recession the Fund has given borrowers added discretionary fiscal stimulus and put less emphasis on financial austerity (Ban 2015; Ostry, Lounganiand Furceri 2016). Conversely, other scholarship finds that when countries participate in IMF arrangements, poverty increases and income distribution worsens (Easterly 2003; Forster et al. 2019; Garuda 2000; Oberdabernig 2013: 123; Vreeland 2002). Still, others indicate that while the Fund’s poverty reduction programmes have no adverse effects on the poor in borrower countries, they have limited impact on lessening poverty (Hajro and Joyce 2009; Lang 2021).

This paper adds to the IMF and poverty literature by disaggregating loan arrangement conditions. Employing instrumental modelling to account for non-random IMF selection for 81 developing countries from 1986 to 2016, and consistent with the literature (Garuda 2000; Oberdabernig 2013; Pastor 1987; Vreeland 2002), we find that developing countries operating under IMF loans experience higher poverty rates in general. However, and building on previous research (Easterly 2003; Krueger et al. 2003; Reinsberg et al. 2019a), we also report that IMF conditions have different effects on poverty. The IMF codes loan conditions as structural (i.e. structural performance criteria or structural benchmark) or stabilisation reforms (i.e. quantitative performance criteria or indicative benchmark) (Reinsberg et al. 2019a). We find that loans with structural conditions tend to increase poverty, while loans with stabilisation conditions usually have little measurable impact. Our results are consistent over the short and medium term and robust to different model specifications.

We contend that structural reforms involve deep and comprehensive market-oriented changes to the economy that tend to raise unemployment, lower government revenue, increase costs of basic services, and restructure tax collection, pensions, and social security programmes, leading to worsened poverty. Additionally, when we disaggregate structural reforms to their specific conditions, we find that nearly all have statistically significant and harmful effects, providing further evidence that structural reforms raise rates of poverty.

Conversely, stabilisation reforms and their disaggregated conditions appear to have limited impact on poverty. Although stabilisation policies including cutting government spending, raising interest rates, and repaying debts cause economic pain, the IMF sets broad targets on macroeconomic indicators linked to stabilisation reforms, providing the borrower more policy discretion relative to structural reforms (Grabel 2017; Reinsberg et al. 2019a). As recent work has shown (Ban 2015; Clift 2018; Ostry et al. 2016), the IMF has experienced an evolution of ideas toward more discretionary fiscal stimulus and gradual fiscal austerity. Moreover, given that the poor represent a large share of the electorate in developing countries (Geddes 1994), governments with greater policy discretion hold political incentives to cut government spending, as part of fiscal consolidation policies, that fall less heavily on those near the poverty line, and especially during election years (Hübscher 2016; Hübscher et al. 2020). Further, and contrary to structural policies, studies have found that stabilisation reforms may not be that contractionary over the medium term (Alesina and Perotti 1995) and the higher borrowing costs associated with debt issues may be small and temporary (Panizza et al. 2009), or short-lived (Borensztein and Panizza 2009), potentially limiting the impact of stabilisation measures on poverty.

Our findings hold implications for policymakers. First, based on our sample of countries and years, approximately 1.28 billion people are categorised as impoverished Footnote 1 on average per year, reflecting about 32.7% of the cases. The large number of poor people suggests the importance of IMF-poverty research. Second, the fact that no empirical work has fully tested the influence of all different conditional arrangements on poverty reinforces the benefits of disaggregating fund programmes to show the adverse consequences of structural conditions and the limited impact of stabilisation policies. Third, our research contributes to the globalisation and the poor debate. Although the IMF claims that it supports poverty reduction (IMF 2021), much globalisation work stresses the challenges faced by the poor because of open-market programmes (Ha 2012; Huber et al. 2006; Reuveny and Li 2003; Rudra 2002). Building on previous studies indicating that international pressures hurt the poor (e.g. Oberdabernig 2013), and that stabilisation and structural reforms play varying roles (Reinsberg et al. 2019a, b), our results show how international pressures, as reflected by IMF conditions, can hurt the poor but that what matters most for addressing poverty is whether countries initiate structural reforms.

The impact of the IMF on development in the developing world has drawn significant attention, with much of the interest deriving from the fact that, since the 1980s, debt crises and capital shortages have increased demand for IMF services (Vreeland 2003a: 12‒16). The growing demand for IMF resources has also sparked debate about the conditions borrowing countries agree to in their Letters of Intent (Babb 2003: 10‒11; Babb and Buira 2005: 64; Vreeland 2003b: 338). While some argue that loan conditionality programmes improve economic growth and income standards for borrowers (Atoyan and Conway 2006; Killick 1995), or promote economic benefits for the poorest countries (Bird and Rowlands 2016) or for long-term users of the fund (Bas and Stone 2014), opponents charge that IMF programmes reduce growth rates (Dreher 2006) and delay recovery for years (Blyth 2013; Stiglitz 2002).

Several studies also show that politics affect IMF loan conditions (Babb 2003; Copelovitch 2010; Stone 2008; Dreher et al. 2015). Although the IMF appeared to respond to the criticisms and began borrower ‘ownership’ programmes in the 2000s (Bird and Rowlands 2016: 12), many studies indicate that IMF loans continue to harm borrower states (Kentikelenis et al. 2016; Nelson 2014b; Stubbs and Kentikelenis 2018; Vetterlein 2015). Given the controversies surrounding the fund, and the economic results in borrower states, the question we ask is what are the effects of the IMF on poverty in the developing world?

In the literature, previous research has reached varying conclusions about the impact of IMF programmes on poverty. Some studies find that IMF loan arrangements contribute to increased poverty. Pastor (1987) and Vreeland (2002), for example, show that participation in IMF programmes worsens income distributions, especially for the poor and the labour class, which can increase rates of poverty. Similarly, Garuda (2000) reports a deterioration in income distribution but only in countries where external imbalances were severe prior to IMF programmes. Others note more mixed results for the IMF and poverty. While Oberdabernig (2013) finds that IMF loans lead to a rise in poverty but only during the first 2 years of a fund programme, Footnote 2 Easterly (2003: 362) shows that IMF programmes lower the growth elasticity of poverty, meaning that ‘economic expansions benefit the poor less under structural adjustment, but at the same time economic contractions hurt the poor less’. By contrast, Lang (2021) observes that IMF concessional arrangements have no substantial effects on poverty rate, a finding also supported by Hajro and Joyce (2009) who show that fund programmes have no significant direct impact on poverty. Footnote 3

Other studies consider how IMF loan arrangements affect policy areas that indirectly impact poverty rates. Rickard and Caraway (2019), for example, observe that public sector reforms in a fund arrangement significantly reduce government spending on public sector wages. Similarly, Stubbs and Kentikelenis (2018) maintain that the practice of conditionality affords international financial institutions including the IMF and World Bank with substantial policy influence on borrower governments’ social expenditures. Relatedly, Forster et al. (2019) report that fiscal policy reforms that limit government expenditure, mandate trade and capital account liberalisation as well as financial sector reforms, and constrain external debt have adverse distributional consequences. They reveal that increases for the top income decile drive the distributional consequences, whereas debt-related issues lower the income share of the bottom quintile. Lastly, Forster et al. (2020) find that structural adjustment policies tied to labour market reforms lower health system access and increase neonatal mortality.

Although prior research that directly (or indirectly) investigated the IMF’s effects on poverty provided many useful insights, none directly and fully considered the numerous conditions contained within IMF loan arrangements that could impact poverty rates in borrower states. Specifically, we argue that IMF loans containing structural conditions support increased poverty while loans with stabilisation conditions are less likely to affect poverty.

Before comparing the specific policy prescriptions within any arrangement, we first distinguish between condition types. The IMF identifies loan conditions as under structural or stabilisation terms. Structural arrangements include structural performance criteria or structural benchmarks, while stabilisation conditions contain quantitative performance criteria or indicative benchmarks (Reinsberg et al. 2019a). The explicit structural factors normally include trade, financial, capital account, tax, and labour reforms, institutional restructurings, as well as privatising state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Hakro and Ahmed 2006; Lora 2012; Morley et al. 1999). In contrast, the IMF (2018) identifies stabilisation reforms as ‘macroeconomic variables under the control of the authorities, such as monetary and credit aggregates, international reserves, fiscal balances, and external borrowing’, a classification also applied in political economy research (Easterly 2003; Kentikelenis et al. 2016; Krueger et al. 2003).

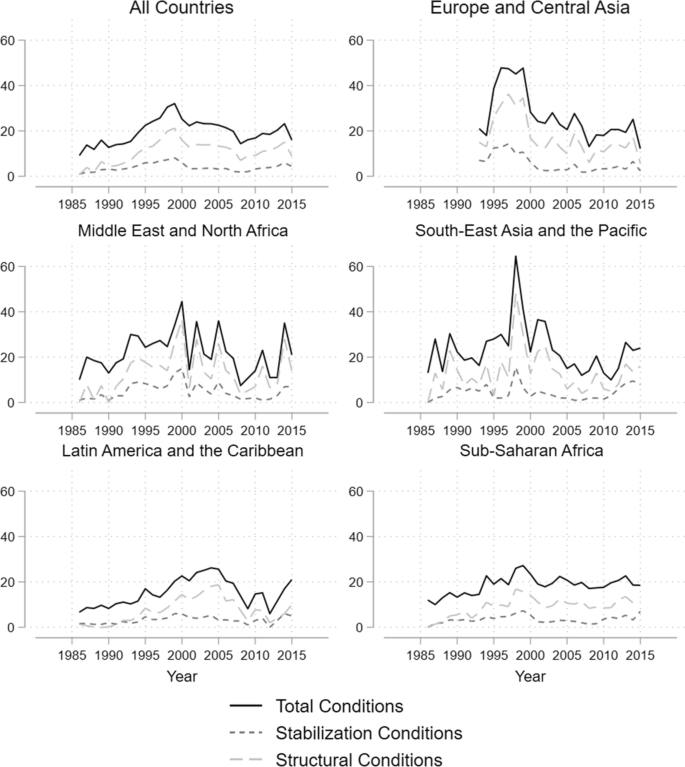

Differentiating between structural and stabilisation conditions, as the IMF and literature do, is critical because of the varying effects the conditions have on borrower states. Building on earlier work (e.g. Easterly 2003; Krueger et al. 2003; Lora 2012), we maintain that structural reforms contain deep and comprehensive changes involving trade and exchange policies, labour reforms, privatisation, financial/fiscal sector issues, revenue and tax policies, and/or institutional reforms. These reforms advance free market commitments to limit the role of the state, and favour government structures that uphold the rule of law and property rights (de Soto 2000). According to Reinsberg et al. (2019a: 1224), structural conditions ‘seek to transform countries’ political economies via deregulation, liberalization, and privatization’. Because they are comprehensive, the reforms contain intrusive conditions that inhibit borrowers from modifying them to mitigate their negative effects on poverty. Indeed, such insights build on Easterly (2005), who argues that structural reforms encroach on borrower sovereignty. We present the evolution of structural and stabilisation loan conditions across time and disaggregated by regions in Fig. 1.

Our theoretical mechanism linking structural policies and poverty relies on the reforms’ effects on raising unemployment, lowering government revenue (and, by extension, social spending), increasing costs of basic services, and restructuring of tax collection, pensions, and social security. Looking first at privatisation, the sale of SOEs to private firms leads to the sacking of redundant state workers, contributing to higher unemployment, raising poverty rates (Beinen and Waterbury 1989). Privatisation also leads to much higher prices for public services (e.g. water, electricity, etc.), as private firms seek to earn monopoly rents in sectors that have barriers to entry, driving more people into poverty (Kurtz and Brooks 2008). Footnote 4

Similarly, equalising income tax rates under regressive tax reforms and a more flexible labour market are also likely to increase poverty (Morley et al. 1999; Rudra 2002). The ‘Washington Consensus’ has long championed lower tax rates for entrepreneurs and higher consumption-based taxes (e.g. value-added taxes) to promote job creation and boost revenues (Williamson 1990). Consumption taxes take a much higher share of the poor’s disposable income. Likewise, the IMF has promoted abolishing taxes on the repatriation of foreign profits to attract capital from abroad. Such policies reduce government revenues, potentially lowering social spending resources for the poor.

Labour reforms are also likely to increase poverty. Previous research has shown that creating a more flexible labour market facilitates the hiring and firing of workers and the lowering of wages for lower-skilled employees (Rudra 2002). Unemployment plays a role in increasing poverty but the fall in wages for less-skilled employees is also critical for people living on the margins. Our labour reforms’ expectation coincides with Rickard and Caraway (2019), who find that IMF public sector conditions lower government spending on public sector wages, contributing to higher poverty rates. Further, pension and social security reforms also tend to follow with a more flexible labour force, again placing the more marginalised workers at risk of falling into the poor ranks.

Trade and institutional changes also affect poverty. Trade receives much attention, as the change from manufacturing for domestic consumers to the global market, and competition for subsistence farmers, contributes to job losses especially for the poor (Frieden 1991). Footnote 5 Contrary to the Heckscher–Ohlin model that developing countries well-endowed with unskilled labour benefit from freer trade, opening markets favours the wealthy at the expense of the poor (Reuveny and Li 2003). Additionally, the promotion of free trade zones, and reduction in tariffs and import duties decreases government revenues available for aiding the poor. The lifting of government-subsidised price controls, also tied to freer trade, raises costs for all consumers but the price hikes again fall disproportionately on the poor (Manzetti 1999). The enforcement of property rights also tends to preserve the interests of an influential minority (Amendola et al. 2013). In Chiapas, Mexico, for example, property rights enforcement, as part of the free trade pact, required common land decampment, forcing many to turn to the informal economy (Kus 2010), increasing their risk of exploitation (Prahalad and Hammond 2002) and raising the specter of higher poverty rates (de Soto 2000). Informal sector workers also have less access to government social spending and retirement funds, increasing their likelihood for poverty.

Financial and fiscal reforms connected to structuralism, which under some circumstances the IMF codes as stabilisation reforms, Footnote 6 are generally associated with the creation of institutions and rules. Financial reforms typically enforce compliance and appoint international auditors to restrict lending from banks with a high percentage of bad loans, promote international practices, and support central bank independence. Fiscal reforms tend to endorse fiscal responsibility laws, establish treasury department functions, certify monthly payrolls, and monitor spending by local governments. Unlike other structural policies, these reforms do not appear to have a direct effect on poverty. In fact, the policies may help reduce corruption, which could indirectly help the poor as government resources go where they are intended and not to serve political cronies.

In contrast to structural reforms, stabilisation policies typically include measures that cut government spending, reduce the money supply, and decrease domestic and external debt to achieve macroeconomic stabilisation (Bird and Rowlands 2016: 40; IMF 2016). Unlike structural reforms, governments under stabilisation reforms can generally pursue a range of alternatives to meet the conditions set by the IMF that are less likely to impinge on borrower sovereignty (Easterly 2005; Reinsberg et al. 2019a).

Beginning with government spending cuts (i.e. fiscal issues), such reductions could increase poverty, as developing countries adopt austerity policies to address inflation, debt arrears, and fiscal imbalances (Végh and Vuletin 2015). Lower expenditure on social programmes is most painful for poorer households (Stubbs and Kentikelenis 2018). However, social spending does not have to contract to the point that it pushes many more people into poverty. As Reinsberg et al. (2019a: 1232) note, ‘stabilization conditions do not oblige governments to enact specific reforms but leave them with some discretion in how to achieve economic policy objectives’. Borrower countries also have political incentives not to implement fiscal consolidation policies that substantially increase poverty, and especially during election years (Hübscher 2016; Hübscher et al. 2020), as the poor comprise a sizable portion of the electorate (Geddes 1994).

Stabilisation measures also include monetary and debt policies to address financial difficulties. Among the monetary policies (i.e. financial reforms), the IMF favours currency boards to restrict currency manipulation by monetary authorities and raise foreign net reserves (IMF 2004). Related to tying monetary authorities’ hands, the IMF also backs policies to reduce external and internal debt arrears, imposing curbs on available credit sources. These monetary and debt measures typically raise interest rates, increasing the cost of borrowing, and making it more expensive for businesses to expand. However, the government has some flexibility in how it addresses financial matters and ‘may renegotiate the terms of existing debt contracts to ease debt service … [or] take measures to promote economic growth, which reduces the debt-to-GDP ratio’, lessening the financial burden on those near the poverty line (Reinsberg et al. 2019a: 1232). Moreover, although the rate hikes could lead to higher unemployment, the rising borrowing costs associated with debt issues may be small and temporary (Panizza et al. 2009), or short-lived (Borensztein and Panizza 2009), limiting their effects on poverty.

Additionally, it is not clear that households near the poverty line will acquire new debt. Big ticket purchases are likely out of the reach of the near-poor, negating increased interest rates. Of course, if they are already borrowers and the higher interest rates are applied retroactively on the existing loans, poverty rates could rise. But higher interest rates may not have the same impact for those near the poverty line as they would incur with structural changes to the economy. Some studies also find that stabilisation policies that reduce budget deficits and domestic credit, and increase the real interest rate, produce higher GDP, lower inflation, and improve the current account balance (Doroodian 1994). Economic growth is key here as ‘most authors agree that economic growth is fundamental for poverty reduction’ (Oberdabernig 2013: 115).

Moreover, the evolution of ideas held by IMF staff members indicates the greater flexibility for borrowers particularly with stabilisation policies. From the 1980s to early 2000s, IMF staff members who supported shock therapy appeared to hold the most influence on loan arrangements (Chwieroth 2008). Chwieroth (2014) argues that the staff’s normative orientations and its common academic training favoured conditionality, with stricter terms for borrowers whose policymakers (or officials) appeared indifferent to the staff’s orientations or who held different professional ties. Likewise, Nelson (2014a) showed that shared economic beliefs between the IMF staff and management and top policymakers in borrower countries affected loan size, conditionality, and enforcement, with market-oriented reforms carrying the day.

However, in the early 2000s and into the Great Recession, a backlash erupted against the IMF, with some arguing that the staff had changed its perspectives regarding strict adherence to fiscal austerity (Ban 2015; Barta 2018; Clift 2018). Gradualism, policy flexibility, and discretionary fiscal stimulus that related to stabilisation seemed to take hold as the IMF’s mantra (Ban 2015: 179; Johnson, and Barnes 2015; Ostry et al. 2016: 41). The IMF even began to incorporate social benchmarks into funding guidelines (Vetterlein 2015). Although some scholars contend that IMF programmes still contain procyclical macroeconomic policies that enforce austerity (Grabel 2017: 113; Nelson 2014a, b: 163; Weisbrot et al. 2009), indicating that there is a mismatch of communication and practice for IMF policies (Grabel 2017: 123; Kentikelenis et al. 2016; Mariotti et al. 2017), others remark that the IMF shows ‘greater acceptance of discretionary fiscal stimulus programs’ (Ban 2015: 179), views fiscal consolidation as ‘not a fiscal noose today’ (Ostry et al. 2016: 41), and sees spending-based adjustments as posing limited effects on households below the poverty line (Blyth 2013). Such programme discretion appears to apply mainly to stabilisation policies and not structural reforms (Grabel 2017; Reinsberg et al. 2019a).

Lastly, stabilisation programmes can include measures that boost social spending and social justice, and provide financial benefits to those below the poverty line (Chu and Gupta 1998: 19; Collier and Gunning 1999; Polak 1991: 36). Footnote 7 As Grabel (2017: 128) notes, the IMF places more attention to social spending targets, the poor, and the vulnerable in its support packages, increasing social spending as a percentage of total public spending for all borrowers. Spending cuts also may not be that contractionary, particularly over the medium term (Alesina and Perotti 1995). As Alesina and Ardagna (2013: 20) observe, ‘in some cases spending-based adjustments have been associated with no recession at all, even in the short run, thus producing an expansionary fiscal adjustment.’

Based on the preceding discussion, we propose two hypotheses.

Structural loan conditions imposed by the IMF are likely to increase poverty rates.

Stabilisation loan conditions imposed by the IMF are not significantly related to poverty.