Pointers are one of C++’s historical boogeymen, and a place where many aspiring C++ learners have gotten stuck. However, as you’ll see shortly, pointers are nothing to be scared of.

In fact, pointers behave a lot like lvalue references. But before we explain that further, let’s do some setup.

If you’re rusty or not familiar with lvalue references, now would be a good time to review them. We cover lvalue references in lessons 12.3 -- Lvalue references, 12.4 -- Lvalue references to const, and 12.5 -- Pass by lvalue reference.

Consider a normal variable, like this one:

char x <>; // chars use 1 byte of memorySimplifying a bit, when the code generated for this definition is executed, a piece of memory from RAM will be assigned to this object. For the sake of example, let’s say that the variable x is assigned memory address 140 . Whenever we use variable x in an expression or statement, the program will go to memory address 140 to access the value stored there.

The nice thing about variables is that we don’t need to worry about what specific memory addresses are assigned, or how many bytes are required to store the object’s value. We just refer to the variable by its given identifier, and the compiler translates this name into the appropriately assigned memory address. The compiler takes care of all the addressing.

This is also true with references:

int main() < char x <>; // assume this is assigned memory address 140 char& ref < x >; // ref is an lvalue reference to x (when used with a type, & means lvalue reference) return 0; >Because ref acts as an alias for x , whenever we use ref , the program will go to memory address 140 to access the value. Again the compiler takes care of the addressing, so that we don’t have to think about it.

The address-of operator (&)

Although the memory addresses used by variables aren’t exposed to us by default, we do have access to this information. The address-of operator (&) returns the memory address of its operand. This is pretty straightforward:

#include int main() < int x< 5 >; std::cout On the author’s machine, the above program printed:

5 0027FEA0

In the above example, we use the address-of operator (&) to retrieve the address assigned to variable x and print that address to the console. Memory addresses are typically printed as hexadecimal values (we covered hex in lesson 5.3 -- Numeral systems (decimal, binary, hexadecimal, and octal)), often without the 0x prefix.

For objects that use more than one byte of memory, address-of will return the memory address of the first byte used by the object.

The dereference operator (*)

Getting the address of a variable isn’t very useful by itself.

The most useful thing we can do with an address is access the value stored at that address. The dereference operator (*) (also occasionally called the indirection operator) returns the value at a given memory address as an lvalue:

#include int main() < int x< 5 >; std::cout On the author’s machine, the above program printed:

5 0027FEA0 5

This program is pretty simple. First we declare a variable x and print its value. Then we print the address of variable x . Finally, we use the dereference operator to get the value at the memory address of variable x (which is just the value of x ), which we print to the console.

Given a memory address, we can use the dereference operator (*) to get the value at that address (as an lvalue).

The address-of operator (&) and dereference operator (*) work as opposites: address-of gets the address of an object, and dereference gets the object at an address.

Although the dereference operator looks just like the multiplication operator, you can distinguish them because the dereference operator is unary, whereas the multiplication operator is binary.

Getting the memory address of a variable and then immediately dereferencing that address to get a value isn’t that useful either (after all, we can just use the variable to access the value).

But now that we have the address-of operator (&) and dereference operator (*) added to our toolkits, we’re ready to talk about pointers.

A pointer is an object that holds a memory address (typically of another variable) as its value. This allows us to store the address of some other object to use later.

In modern C++, the pointers we are talking about here are sometimes called “raw pointers” or “dumb pointers”, to help differentiate them from “smart pointers” that were introduced into the language more recently. We cover smart pointers in chapter 22.

Much like reference types are declared using an ampersand (&) character, pointer types are declared using an asterisk (*):

int; // a normal int int&; // an lvalue reference to an int value int*; // a pointer to an int value (holds the address of an integer value)To create a pointer variable, we simply define a variable with a pointer type:

int main() < int x < 5 >; // normal variable int& ref < x >; // a reference to an integer (bound to x) int* ptr; // a pointer to an integer return 0; >Note that this asterisk is part of the declaration syntax for pointers, not a use of the dereference operator.

When declaring a pointer type, place the asterisk next to the type name.

Although you generally should not declare multiple variables on a single line, if you do, the asterisk has to be included with each variable.

int* ptr1, ptr2; // incorrect: ptr1 is a pointer to an int, but ptr2 is just a plain int! int* ptr3, * ptr4; // correct: ptr3 and ptr4 are both pointers to an intAlthough this is sometimes used as an argument to not place the asterisk with the type name (instead placing it next to the variable name), it’s a better argument for avoiding defining multiple variables in the same statement.

Like normal variables, pointers are not initialized by default. A pointer that has not been initialized is sometimes called a wild pointer. Wild pointers contain a garbage address, and dereferencing a wild pointer will result in undefined behavior. Because of this, you should always initialize your pointers to a known value.

Always initialize your pointers.

int main() < int x< 5 >; int* ptr; // an uninitialized pointer (holds a garbage address) int* ptr2<>; // a null pointer (we'll discuss these in the next lesson) int* ptr3< &x >; // a pointer initialized with the address of variable x return 0; >Since pointers hold addresses, when we initialize or assign a value to a pointer, that value has to be an address. Typically, pointers are used to hold the address of another variable (which we can get using the address-of operator (&)).

Once we have a pointer holding the address of another object, we can then use the dereference operator (*) to access the value at that address. For example:

#include int main() < int x< 5 >; std::cout ; // ptr holds the address of x std::cout

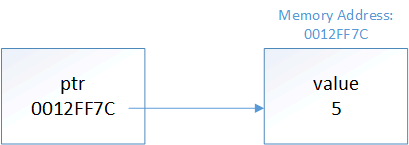

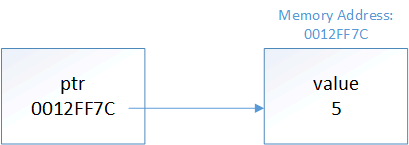

Conceptually, you can think of the above snippet like this:

This is where pointers get their name from -- ptr is holding the address of x , so we say that ptr is “pointing to” x .

A note on pointer nomenclature: “X pointer” (where X is some type) is a commonly used shorthand for “pointer to an X”. So when we say, “an integer pointer”, we really mean “a pointer to an integer”. This understanding will be valuable when we talk about const pointers.

Much like the type of a reference has to match the type of object being referred to, the type of the pointer has to match the type of the object being pointed to:

int main() < int i< 5 >; double d< 7.0 >; int* iPtr< &i >; // ok: a pointer to an int can point to an int object int* iPtr2 < &d >; // not okay: a pointer to an int can't point to a double object double* dPtr< &d >; // ok: a pointer to a double can point to a double object double* dPtr2< &i >; // not okay: a pointer to a double can't point to an int object return 0; >With one exception that we’ll discuss next lesson, initializing a pointer with a literal value is disallowed:

int* ptr< 5 >; // not okay int* ptr< 0x0012FF7C >; // not okay, 0x0012FF7C is treated as an integer literalPointers and assignment

First, let’s look at a case where a pointer is changed to point at a different object:

#include int main() < int x< 5 >; int* ptr< &x >; // ptr initialized to point at x std::cout ; ptr = &y; // // change ptr to point at y std::cout The above prints:

In the above example, we define pointer ptr , initialize it with the address of x , and dereference the pointer to print the value being pointed to ( 5 ). We then use the assignment operator to change the address that ptr is holding to the address of y . We then dereference the pointer again to print the value being pointed to (which is now 6 ).

Now let’s look at how we can also use a pointer to change the value being pointed at:

#include int main() < int x< 5 >; int* ptr< &x >; // initialize ptr with address of variable x std::cout This program prints:

5 5 6 6

In this example, we define pointer ptr , initialize it with the address of x , and then print the value of both x and *ptr ( 5 ). Because *ptr returns an lvalue, we can use this on the left hand side of an assignment statement, which we do to change the value being pointed at by ptr to 6 . We then print the value of both x and *ptr again to show that the value has been updated as expected.

When we use a pointer without a dereference ( ptr ), we are accessing the address held by the pointer. Modifying this ( ptr = &y ) changes what the pointer is pointing at.

When we dereference a pointer ( *ptr ), we are accessing the object being pointed at. Modifying this ( *ptr = 6; ) changes the value of the object being pointed at.

Pointers behave much like lvalue references

Pointers and lvalue references behave similarly. Consider the following program:

#include int main() < int x< 5 >; int& ref < x >; // get a reference to x int* ptr < &x >; // get a pointer to x std::cout This program prints:

555 666 777

In the above program, we create a normal variable x with value 5 , and then create an lvalue reference and a pointer to x . Next, we use the lvalue reference to change the value from 5 to 6 , and show that we can access that updated value via all three methods. Finally, we use the dereferenced pointer to change the value from 6 to 7 , and again show that we can access the updated value via all three methods.

Thus, pointers and references both provide a way to indirectly access another object. The primary difference is that with pointers, we need to explicitly get the address to point at, and we have to explicitly dereference the pointer to get the value. With references, the address-of and dereference happens implicitly.

The address-of operator returns a pointer

It’s worth noting that the address-of operator (&) doesn’t return the address of its operand as a literal. Instead, it returns a pointer containing the address of the operand, whose type is derived from the argument (e.g. taking the address of an int will return the address in an int pointer).

We can see this in the following example:

#include #include int main() < int x< 4 >; std::cout On Visual Studio, this printed:

With gcc, this prints “pi” (pointer to int) instead. Because the result of typeid().name() is compiler-dependent, your compiler may print something different, but it will have the same meaning.

The size of pointers

The size of a pointer is dependent upon the architecture the executable is compiled for -- a 32-bit executable uses 32-bit memory addresses -- consequently, a pointer on a 32-bit machine is 32 bits (4 bytes). With a 64-bit executable, a pointer would be 64 bits (8 bytes). Note that this is true regardless of the size of the object being pointed to:

#include int main() // assume a 32-bit application < char* chPtr<>; // chars are 1 byte int* iPtr<>; // ints are usually 4 bytes long double* ldPtr<>; // long doubles are usually 8 or 12 bytes std::cout The size of the pointer is always the same. This is because a pointer is just a memory address, and the number of bits needed to access a memory address is constant.

Much like a dangling reference, a dangling pointer is a pointer that is holding the address of an object that is no longer valid (e.g. because it has been destroyed).

Dereferencing a dangling pointer (e.g. in order to print the value being pointed at) will lead to undefined behavior, as you are trying to access an object that is no longer valid.

Perhaps surprisingly, the standard says “Any other use of an invalid pointer value has implementation-defined behavior”. This means that you can assign an invalid pointer a new value, such as nullptr (because this doesn’t use the invalid pointer’s value). However, any other operations that use the invalid pointer’s value (such as copying or incrementing an invalid pointer) will yield implementation-defined behavior.

Dereferencing an invalid pointer will lead to undefined behavior. Any other use of an invalid pointer value is implementation-defined.

Here’s an example of creating a dangling pointer:

#include int main() < int x< 5 >; int* ptr< &x >; std::cout ; ptr = &y; std::cout // y goes out of scope, and ptr is now dangling std::cout The above program will probably print:

5 6 6

But it may not, as the object that ptr was pointing at went out of scope and was destroyed at the end of the inner block, leaving ptr dangling.

Pointers are variables that hold a memory address. They can be dereferenced using the dereference operator (*) to retrieve the value at the address they are holding. Dereferencing a wild or dangling (or null) pointer will result in undefined behavior and will probably crash your application.

Pointers are both more flexible than references and more dangerous. We’ll continue to explore this in the upcoming lessons.

What values does this program print? Assume a short is 2 bytes, and a 32-bit machine.

#include int main() < short value< 7 >; // &value = 0012FF60 short otherValue< 3 >; // &otherValue = 0012FF54 short* ptr< &value >; std::cout

0012FF60 7 0012FF60 7 0012FF60 9 0012FF60 9 0012FF54 3 0012FF54 3 4 2

A brief explanation about the 4 and the 2. A 32-bit machine means that pointers will be 32 bits in length, but sizeof() always prints the size in bytes. 32 bits is 4 bytes. Thus the sizeof(ptr) is 4. Because ptr is a pointer to a short, *ptr is a short. The size of a short in this example is 2 bytes. Thus the sizeof(*ptr) is 2.

What’s wrong with this snippet of code?

int v1< 45 >; int* ptr< &v1 >; // initialize ptr with address of v1 int v2 < 78 >; *ptr = &v2; // assign ptr to address of v2The last line of the above snippet doesn’t compile.

Let’s examine this program in more detail.

The first and fourth lines contain standard variable definitions, along with an initialization value. Nothing special here.

On the second line, we’re defining a new pointer named ptr , and initializing it with the address of v1 . Remember that in this context, the asterisk is part of the pointer declaration syntax, not a dereference. So this line is fine.

On line five, the asterisk represents a dereference, which is used to get the value that a pointer is pointing to. So this line says, “retrieve the value that ptr is pointing to (an integer), and assign it the address of v2 . That doesn’t make any sense -- you can’t assign an address to an integer!

The fifth line should be:

This correctly assigns the address of v2 to the pointer.